This week marks the fourth anniversary of Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson’s passing. We definitely wouldn’t be running this website were it not for Christopherson and his influence on music the world over, and it’s not at all an exaggeration to say that our personal lives would be a shade duller, our eyes a mite dunner, our souls a touch poorer had he never begun working with Cosey Fanni Tutti, Genesis P-Orridge, and Chris Carter, or later with Jhonn Balance and others in the Coil continuum. His absence is something we still wrestle with as fans and listeners, and it’s in that spirit that we thought we’d reflect on some of the reasons why he’s so missed, and still so loved.

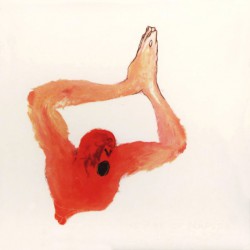

The Ape of Naples

Although he was a distinctive and dynamic artist in his own right, an overwhelming amount of the work Sleazy is known for is collaborative. Specifically, his partnership with Jhonn Balance is arguably his greatest legacy, which is what makes the final Coil album simultaneously amazing and heartbreaking. Culled from more than a decade of recordings (including the infamous Backwards sessions recorded for Trent Reznor’s Nothing Records in the 90s), Christopherson remixed and reworked all the disparate elements into a stunning elegy for his creative partner and friend. Of course the most telling aspect of The Ape of Naples is how much the album speaks to Balance’s passing in his own words, the artfulness of its construction so complete that it can be difficult to remember that Sleazy finished the record after Jhonn’s death. A loving tribute to a departed friend at the time of its release, it took on new dimensions at the time of Christopherson’s own death and now fittingly, tragically, stands as the last proper Coil record.

Designing Industrial Culture

A case could be made that the visual aesthetics of what would become industrial culture owe more to Christopherson than anyone else, if more for reasons of consolidation than anything else. From what we’ve gathered, design in TG was somewhat collaborative, given each member’s background in art of some stripe previous to forming the band (with Gen designing the infamous shock logo). But record design lay with Peter, from the strange medical diagram made somewhat more bestial by way of shadow on Heathen Earth to the “meant to be forgettable” mindhack of 20 Jazz Funk Greats. After TG, in designing albums for Coil, Christopherson would find an ever-widening range of inspirations for designs to accompany post-industrial music: the oddly magisterial gazebo on Horse Rotorvator, the odd mix of sacred and acid-soaked designs in the Gold Is The Metal/Love’s Secret Domain era. A lesser-known tidbit is his design of the still controversial BOY London logo.

His Sleaziness

Being something of a lech feels like an odd thing to be praising someone for, but regardless of his personal proclivities (of which we know very little), Christopherson took his fascination with the sexually aberrant into his work to dramatic effect. At one extreme we can find Coil’s obvious scatological interests. These aren’t necessarily purely perverse: as Kundera and Galas have shown, the question of the holy instantiated in the material must reconcile the problem of shit, something Coil’s gnostic talents were well suited to address. At the other, we can find in Sleazy’s work the exposure of a bourgeois society which damned Throbbing Gristle as “wreckers of civilisation” while still tacitly approving of and remunerating Cosey Fanni Tutti’s sex work within the more capitalistic fields of stripping and porn (a point Cosey’s made plenty of times herself). No where is this illustrated better than in Sleazy and Cosey’s dialog on the Heathen Earth version of “Still Walking”, where Sleazy plays a creep following Cosey home despite her continued rebuffing. “I’ve got to go that way myself…I could keep you company…Later on, if you’re not doing anything…Just because you’re that age doesn’t mean…” It’s an utterly chilling rendering of everyday harassment which is all the more terrifying for its quotidian nature. We’d much rather deal with the shit-smeared maniac: he’s at least being forthright about his wonts.

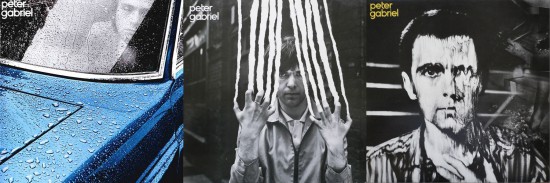

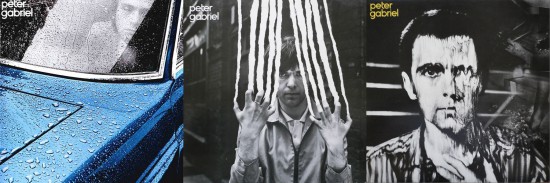

The covers of Peter Gabriel I, II, III

Christopherson’s work with pioneering English design group Hipgnosis is well-documented but fascinating specifically because we have no idea how much of their work can be credited to Sleazy. The firm famously did artwork and design for Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, T. Rex, Black Sabbath and a host of others, but was always credited to the studio rather than any individual. That said, we do have it from various sources that the artwork for Peter Gabriel’s first three eponymous solo albums is largely attributable to Sleazy. While the iconic cover images for II and III speak to his penchant for the disturbing and distorted, the cover for I is equally unsettling, the image of Gabriel isolated and alone standing as a testament to Christopherson’s largely unheralded skill as a still photographer.

“Valley of the Shadow of Death” and “After the Fall”

In spite of the wonderful work done by various interviewers and researchers (plug: go buy Drew Daniels’ enlightening 33 1/3 book about 20 Jazz Funk Greats) it’s still never been totally clear who did what in Throbbing Gristle. At least part of that comes from the group’s creative MO, which sought to eschew traditional ideas of musical form and tradition and tap into baser, instinctual techniques of composition and improvisation; anyone could be doing anything on a given TG song. Part of what makes “Valley of the Shadow of Death” and “After the Fall” so fascinating then is the insight we can glean from them as Christopherson solo compositions in the context of Gristle. The former is an example of the found sound and cut up vocals that permeated the classic TG records, minus any other melodic elements they typify the anti-musical elements of the group’s work. In sharp contrast the latter is built around a simple, sad piano motif that barely manages to surface from the oppressive manipulated sounds surrounding it. Separated by almost thirty years, the songs contain multitudes, and far from explaining anything they add to the questions that have kept Throbbing Gristle’s particular methods of collaboration so compellingly obscure.

Broken

We’ve written at length about the Broken film Christopherson created to accompany the NIN release of the same name, but it (along with the somewhat abortive Coil sessions for Nothing Records) has earned a spot in history, if only for representing a collaboration between one of the people responsible for creating industrial music and the person who transformed that template into more widespread success and fame than anyone else. Christopherson’s sensitive and mixed reaction to the film’s legacy is well worth a read.

NIN – Broken [HQ Version] by LaTo59

His Other Video Work

There was recently a not insignificant amount of snark floating about industrial circles concerning the discovery that Dave “Rave” Ogilvie had mixed “Call Me Maybe”, the implication being that a man most known for his groundbreaking work with Skinny Puppy was debasing himself by working on such a trifle. Leaving aside reductive presumptions of value concerning pop music, the incident drew attention to the fact that plenty of “underground” musicians and artists make their livings in the very above-ground realms of the media in which they earned their credibility. Christopherson is another great example of this, and his lengthy credits as a music video director raise intriguing questions about where the line between artistic vision and professionalism sits. Sure, it’s easy to imagine a legend like Sleazy sinking his teeth into a project like “Broken”, or tunes by Soft Cell, The The, or even Erasure. But what about videos for Bad Company? Van Halen? Level 42? Were these just another day at the office or were some of the aesthetics which drove TG and Coil albums forward somehow present in these? This is of course an unanswerable question (none of us is the same person at the club or onstage as we are at work or behind the lens), but it’s one we keep mulling over each time we learn about another video credit (“I wonder how he got along with the fellows from Godsmack…”).

Form Grows Rampant

The sole release from Sleazy’s Threshold HouseBoys Choir was Form Grows Rampant, a collection of electronic compositions made in collaboration with Danny Hyde. The music on THBC is quite good, relying on computer manipulated vocals and field recordings Christopherson collected in his journeys through his adopted home of Thailand. However, it’s the movie that accompanied the CD release that has the most lasting impact; footage of rituals performed at a vegetarian festival in Krabi Town rendered in glorious slow motion hypnotically draw in the viewer, the ecstasy of the event translated through subtle visual manipulation as the rites themselves become increasingly extreme. It’s fascinating specifically because it eschews an anthropological perspective, an example of Sleazy’s voyeurism turned in on itself to become an abstract kind of participation.

A Gay Pioneer

Coil weren’t quite the first openly gay band in existence, but they certainly were one of the first (if not the first) to examine gay male sexuality within their actual music (beating Bronski Beat out by a couple of years). We’ve also heard it reported that their 1985 “Tainted Love” single was the first musical AIDS charity release. Thirty years on this all sounds utterly rote, with the Eddie Mercury mega benefit concert a distant memory and an incalculable list of out pop stars experiencing mainstream success, but the first half of the 80s was another era entirely, in which HIV+ children were being expelled from school and in which it was de rigeur to open a comedy routine with jokes not even about gay men but in which their mere existence was the punchline. While queer sexuality wasn’t the sum total of Christopherson’s oeuvre (though its attention to sexuality in toto can’t be denied), he deserves credit for being an early voice for it.

Desertshore

The Throbbing Gristle recreation of Nico’s Desertshore bizarrely became a reflection of The Ape of Naples; while the original sessions were recorded in 2007 and featured the whole line-up, it was Sleazy who sought to complete them after the group’s implosion. It would be Chris and Cosey who finished the record with assistance from numerous guest vocalists including Antony Hegarty, Blixa Bargeld and Marc Almond, and like Ape before it, the posthumous release would end up speaking to the legacy of the artist who never heard it in its final form. As a goodbye to a friend it’s stunning, as a version of Sleazy’s own creative vision it offers a sampling of his whimsy, his emotion and his capricious artistic spirit.

His Wit And Warmth

We never met Sleazy, and so apart from his work our only impressions of him as a person come from interviews and second-hand anecdotes (like asking a photographer who’d shot a Coil show if he’d like to come over to his hotel room to take some more photos). Those interviews and conversations speak to someone with a razor wit and a genuine and honest engagement with the world of music and ideas to which he contributed. In one of his final interviews we find him happy to be releasing music new and old, and still affected by the impact his music’s had on people’s lives. He even resurfaces in the comments below after a query about his health: “I take great comfort in knowing, with certainty, that thing that makes us special, able to enrich our own lives and those of others, will not cease when our bodies do, but will be just starting and new (and hopefully even better) adventure…If we don’t get to meet in this Life, maybe in the next you can buy me a beer!” We’re not sure that we can share in his certainty, but if he’s right, first round’s on us.

The Industrialist

Although the word “industrial” doesn’t encapsulate the whole of Peter Christopherson’s various creative endeavours, there are certainly some important lessons we can glean from his contributions to the genre. As an artist who worked in both underground and wholly mainstream capacities, as a technician and skilled musician who often sought to undermine his own ability for the sake of freeing himself creatively, and as a personality who could be deadly serious or brash and campy, he eschewed simple narratives for much grander and more complicated creative pathways. As a founder and patron saint of a musical genre that only made up a portion of his legacy, he teaches us that the borders we put around the art we enjoy are illusory, and that genre and style only hold as much value as we place in them. Sleazy was industrial, and also not industrial at all, and that’s something worth remembering as we reflect on his accomplishments.