“Industrial music is where my heart is. It’s what I love.”

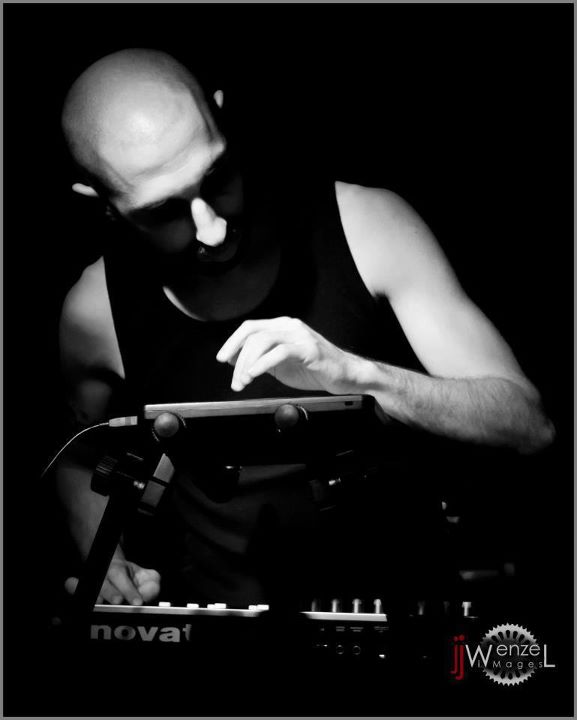

Toronto’s Jairus Khan has been releasing and performing music as Ad·ver·sary since 2005. His explorations into rhythmic noise, power noise and ambient have produced the Bone Music LP and companion album A Bright Cut Across Velvet Sky (both released on Tympanik), and led to tours, remixes and collaborations with the likes of Iszoloscope, Cyanotic, and Everything Goes Cold. As an outspoken advocate of Creative Commons licenses and a keen analyst of the state of industrial culture as a whole, Jairus talked to us about those issues as well as the motives and philosophies underlying his own recordings and performances.

ID:UD: Previous to your move to Toronto, you were a long-time resident at DJ Leslie’s long running Industrial Strength club night in Ottawa. As an artist who was also an active DJ, do you find that one world bled into the other? Do you ever approach making music as a DJ, or DJing as a musician?

Jairus: I’ve been DJing since I was around 16, and making music seriously since I was around 26. I’ve been DJing for half my life, and making music for about a third of the time I’ve been DJing. So it’s a big difference. I still consider myself a DJ first and an electronic musician second. I mean, I love what I’m doing with Ad·ver·sary. I love it. I’m just not as good of an electronic musician as I am a DJ. I haven’t put in enough time yet. I’m a much more diverse DJ than I am a musician, I’m a much more technically skilled DJ than I am a musician, and I’m much more confident as a DJ than I am as a musician.

With all of that said, as a DJ I got sick of DJs-making-music-for-other-DJs a long time ago, which was a good headspace to be in when I started making my own music. I had already spent years examining the things I liked and disliked about electronic music, and having those ideas challenged by the people I spun with and the audiences I spun for. I knew what I wanted to hear, I knew the things that ruined songs for me, and I knew what ground I didn’t want to re-tread.

I don’t make music as a DJ. I don’t write songs for the dancefloor, or for other DJs to enjoy. I think the reason that I feel that freedom is because being a DJ primed me to understand the dangers of being concerned with what other DJs think of your music.

ID:UD: Without meaning to sound reductive, then, if not for DJs do you write with a particular audience or goal in mind?

Jairus: Yes and no. I try to communicate a story, so there’s certainly a goal there. It’s more complicated when it comes to audiences.

Like, “International Dark Skies” is about trying to deal with difficult things during winter, and about how completely isolating and beautiful city streets under fresh snow are at four in the morning. There’s this quality to them that isn’t like anything else. I’d go for walks at night because I was upset, or I couldn’t sleep, or I needed to be alone. That’s what that song is about. Feeling that stillness as a visceral, physical thing.

So there was absolutely an audience in mind when I was writing it: People in difficult times, alone on a winter night.

ID:UD: Ad·ver·sary is a good example of the phenomenon where a lot of acts who are fairly disparate soundwise but are united under the industrial umbrella remix and collaborate with one another. You don’t have a lot in common with, say, Cyanotic on the surface, but you’re both “industrial” bands. How does being part of industrial influence your work, and who you work with?

Jairus: Industrial music is where my heart is. It’s what I love. Sean from Cyanotic and I don’t work that often with the same palette, but we come from the same tradition. We love the same movies. We could spend all day talking about how important crossover acts like Pailhead or Lard are.

What punk rock taught everyone is that you only need to know how to play three chords to put out an album. What industrial music taught me is that you don’t even need to know one. Experimentation, aesthetics, collage and context are what you need to learn. That’s why acts like Cabaret Voltaire and Cubanate can fit in the same genre.

Being part of industrial doesn’t much influence who I work with, aside from the obvious impact of defining the people that I come into regular contact with. It influences the way I work all the time, though. If I didn’t love industrial music, I don’t think I’d spend so much time trying to find new ways to arrange familiar sounds, to make art from noise. I wouldn’t be excited by it. I wouldn’t even know it was possible.

ID:UD: As someone who has always used software to make music, how has being a “computer musician” for lack of a better term influenced your process? Beyond the obvious differences from hardware and the question of access to tools, how much of what Ad·ver·sary is sonically has been governed by that?

Jairus: That’s tough to answer, because I’ve never known anything else. It’s kind of like asking how much of my sex life is governed by being queer, or how much of my communication is governed by speaking English. All of it? None of it? It depends on the metrics you think are important, I guess.

I’m not a hardware guy. I don’t fetishize modular synthesis or circuit bending or analog filters. But I do know computers inside and out, and it seemed like it would be a waste of time to start over from zero in the analog world. I don’t have the time or money to learn how to do all the things I already know how to do, except with a new set of tools that break down twice as often and cost ten times as much.

When I was a teenager, I used to make these terrible little demoscene tracks using Mod Tracker and Impulse Tracker. They were awful, but I loved the process because it was keyboard driven and precise, like programming. There wasn’t anything analog in the way, like trying to worry about hitting the drums on time or thinking about how much force to use on the keyboard or making sure that the fader was in exactly the right place. If you wanted to change those things, it was just a hex value to modify.

I don’t feel as strongly about that as I used to, but I enjoy that my creative process is primarily interfaced through a keyboard, mouse and monitor. I have MIDI controllers which get used a lot live, but when I’m programming drums or trying to fine-tune a sound, I want the precision and workflow that I’ve only ever been able to get through a computer.

“…when you’re on stage, your job — your only job — is to be interesting to the people watching.”

ID:UD: Ad·ver·sary has toured and played various festivals, always with you as the solo live member. In our experience, you’ve also gone out of your way to avoid the “staring at a laptop” stage show that is endemic of many one-person projects. What’s the importance of live performance to you, and how do you keep it interesting for the audience?

Jairus: I’ve been lucky enough to work with a lot of extremely talented artists. I can’t tell you how many of those artists let me down when I booked them and witnessed how little they actually do live. It’s the same when you play festivals and you’re there for a dozen other bands doing soundcheck, you get to see how many bands have controllers and keyboards that literally don’t do anything. And it’s insulting, you know? Not just because they’re not doing anything live, but because they have so little regard for the audience that they can’t even be bothered to put together a convincing fake.

You nailed it with your question about keeping it interesting, because when you’re on stage, your job — your only job — is to be interesting to the people watching. If you’re Autechre, maybe you turn off all the lights because what’s interesting to that audience is listening to differences between the micro-tonal percussive whatever whatever whatever. If you’re Fuck Buttons, maybe you stand in one place and jump up and down for an hour because you’re playing to a party crowd and they want a high-energy environment. If you’re Larvae, maybe you’re a laptop jockey but you’re projecting these incredible high-quality short films for each of your songs. If you’re 5F-X maybe you wear giant alien costumes and do a weirdo puppet show while your music is being played by Winamp. Like, I don’t care. I don’t care how live the music is, as long as you’re giving me something else to hold on to. That’s the importance of live performance to me.

Now, I’m not happy with my stage show. I’m not happy with it as an artist, and I don’t know if I’d be happy with it if I was in the audience. But my stage show has always been the best I can do, at the time that I’m doing it. I switched up and changed my entire workflow because I wanted to get out from behind a laptop. I worked with some great VJs to put together a backing video that doesn’t make me cringe when I watch it like most backing videos do. It has always been as interesting as I can make it.

I have a lot of respect (and jealousy) for acts like iVardensphere. There have been a half-dozen different iVardensphere stagings. Scott with some gear. Three dudes in latex butcher costumes with some gear. Two dudes with some gear and a drummer. Two dudes in costumes with some gear and a stage full of drummers. It’s fantastic. I haven’t figured out how to do that yet. I’ve tried working with a shoegaze/noise guitarist for ambient gigs, but I haven’t figured out how to put on a show like iVardensphere does. I want the music to be the most important part of what I’m doing live, and I have yet to figure out a way to develop a stage show without feeling like I’m compromising that.

Until I figure that out, I’m trying to be as dynamic as I can as a one-man act. I try to build my rig on stage so that I have to move to get from keyboard stand to another. I set my controllers up so that there’s an obvious relationship between what my hands are doing and what you’re hearing. I make sure there is never, ever a laptop screen between myself and the audience.

I want to play show that I would love to watch. I don’t think I’m there yet. We’ll see what happens between now and Kinetik.

ID:UD: Tympanik has established a strong roster in a short space of time, much of which (in our opinion) is doing a great job of pushing certain veins of electronic music forward, and there seems to be a good sense of community between the artists there judging from the amount of collaborations and remixing. How did releasing your stuff with Tympanik come about?

Jairus: I’m lucky to be on a label with as many talented artists as Tympanik. I had originally been speaking to Ant-Zen and a couple other labels about releasing an album with them, but it never totally gelled. Meanwhile, Paul from Tympanik actually heard my demo somewhere and sent me a message, but I never saw it. It ended up in my spam folder. So when I sent Tympanik a message after hearing the first Emerging Organisms compilation, they were like “we were waiting to hear from you!”

“I try really hard to make sure I’m not just listening to industrial music. I try to make sure I’m not just listening to music I’m familiar or comfortable with.”

ID:UD: While there’s a host of genre descriptors that can and have been used to describe your music as Ad·ver·sary (technoid, power noise), your music has always seemed to us to have a broader palette of influences and sounds than is immediately apparent, like the cinematic textures and strings on ‘Friends of Father’ for example. Can you speak to that?

Jairus: Eight or nine years ago I was invited to DJ a goth festival. I started out as a goth/industrial/new-wave DJ before I started playing raves, and the theme of this festival was about celebrating the roots of goth music, so they invited me to open up the festival. On the day of the festival, Johnny Cash dies. I play my set, a lot of proto-goth, batcave stuff, whatever. For my last track, I play Cash’s “Man In Black”. It’s a great song. It’s political. It’s a protest song. Most relevantly to the crowd at the festival, it’s about wearing all black. Right?

I play “Man In Black”. And everyone in the club freezes, and looks at me. And they’re not just looking at me, they’re staring daggers at me. I could have spit on someone and gotten kinder looks. Like, they’re actually trying to kill me through pure force of will. I didn’t think it was going to be a dancefloor hit, but holy fuck did I ever misjudge how bad it was going to go over.

The song ends and I start packing my shit up. No one is making eye contact with me. Everyone is pissed, people are saying “what the fuck was that”, that kind of thing. Anyway. The band that’s playing next goes on stage. They get introduced, and the lead singer walks over and grabs the mic. He puts his foot up on the monitor like he’s in Zeppelin and yells, “This one’s for Johnny Cash!”

And the place goes crazy. Everyone’s cheering like they’re on Oprah and they all won a car.

That’s when it hit me: Not a single fucking person on that dancefloor has ever listened to Johnny Cash. They know he’s the ‘cool’ country singer who covered Nine Inch Nails and Depeche Mode and shot someone in a prison or something. But they’ve never actually owned a Cash record, they’ve never actually listened to a Cash song.

That’s why the goth scene has been stagnant for so long. People are insular, dismissive of anything unfamiliar, and afraid to listen to music that might make them uncool. So you had this whole wave of goth acts that thought the only way to do something new was to retread old ground, but with more attitude.

That’s what’s happening with industrial music now. Industrial acts aren’t influenced by anything other than other industrial acts. The whole scene is crawling up its own ass.

I try really hard to make sure I’m not just listening to industrial music. I try to make sure I’m not just listening to music I’m familiar or comfortable with. In the next month or so I’m going to see Sleigh Bells, Buddy Guy, and Acid Mothers Temple. I get way more excited about those kinds of shows than I do industrial shows. I don’t know noise pop or Chicago blues or Japanese psych rock the way I know industrial music, which means I’m going to hear something new and learn something new at every one of those shows.

So, yeah. I try to draw from a broad set of influences, absolutely. I couldn’t have written “Friends of Father” if I hadn’t listened to the work The Bomb Squad have done in hip hop or the work Angelo Badalamenti has done in film. I wouldn’t have had the vocabulary.

ID:UD: Do you see that trend turning around given the near instantaneous access to all manner of music which is available to kids who are having their formative musical experiences today? Do you think the current relationship between technology and music fosters broader tastes or does it just allow people to drill even deeper into particular isolated niches?

Jairus: That’s tough. The role of a DJ isn’t as important today as it was ten, twenty, or fifty years ago. Not in the same way, at least. There’s not going to be another John Peel. It’ll be another Girl Talk instead.

I think services like Spotify and Turntable.FM and Last.FM show that music is going to be filtered from the bottom-up instead of top-down, the way online news is. People still read the New York Times, but user-driven sites have ten or twenty times as many readers. That’s the direction I’d like to see things go in. There’s just too much music to keep up with. It’s not possible.

A DJ friend of mine used to spend every moment of her free time downloading music from MP3 blogs, listening, sorting, writing scripts to auto-click and auto-download to make things more efficient. It was still too much. It doesn’t matter how much time you have, there’s always more music. Now she pays someone to use those scripts to download music and listen to it, and send her a once-a-week digest of a couple dozen albums that she might like. She still has to sort through those couple dozen, but it’s only a couple dozen a week instead of a couple hundred.

Last.FM knows enough about the music I listen to, Spotify knows enough about the music that’s coming out, and Facebook knows enough about the people who I talk to about music. Eventually they’re going to get their shit together and send me a weekly email of the Top Five New Albums Jairus Is Going To Fucking Love. That’s what I’m waiting for.

“The punk rock scene had a lot more time, effort and care put into keeping things exciting than the industrial scene does, and things still went south there. We’re not magically immune to the dangers of being closed-minded.”

ID:UD: There’s a not inconsiderable number of folks who believe that the scene is in decline, both from the perspective of both the originality of the music being made and the attendance to various shows and club nights. Do you see any connection either real or imagined between those factors, or is this a rose coloured glasses type scenario?

Jairus: It’s a little bit of both. Every scene that I’ve spent a serious amount of time in, when people talked about ‘the golden age’ they were always talking about whenever it was that they got interested in that scene.

When I was more involved with hacking/phreaking everyone talked about how the golden age was back when LOD/MOD were on the scene, which is crazy talk. Phreaking was much more interesting in the 60s, and hacking became a hundred times more interesting after the web changed everything. When I was DJing in the rave scene everyone talked about how the old warehouse parties were better than these big shows with people wearing stupid fun fur. When the cops shut down all those parties people talked about the glory days of the big shows with awesome fun fur everywhere. There are absolutely rose coloured glasses at play anywhere.

With that said, you’d have to be crazy not to think that the scene is in decline, musically or otherwise. You couldn’t watch a sci-fi film in the 90s without tripping over a half-dozen industrial acts. Bands outside the genre like Manson and White Zombie and Orgy were driving traffic to industrial clubs/labels/shops like crazy, and everyone had money to spend because computer nerds could name their own salaries.

When I think about the state of industrial music, there are two quotes I keep coming back to. The first, from Sleazy: “The original idea of Industrial Records was to reject what the growing industry was telling you at the time what music was supposed to be.”

Is that what we’re doing? Is that what you think when you watch the new Nachtmahr video? That it is in any way a rejection of what those musicians are listening to?

The second is from a Dead Kennedys track, “Chickenshit Conformist”:

“Punk’s not dead, it just deserves to die when it becomes another stale cartoon.

A close-minded, self-centered social club, ideas don’t matter, it’s who you know.

If the music’s gotten boring, it’s because of the people who want everyone to sound the same.

Who drive bright people out of our so-called scene until all that’s left is just a meaningless fad.”

Sometimes when I get on stage I just want to play that track over and over with the words projected behind me in ten foot tall letters, you know? The punk rock scene had a lot more time, effort and care put into keeping things exciting than the industrial scene does, and things still went south there. We’re not magically immune to the dangers of being closed-minded. If people don’t demand better than what they’re getting, they won’t get it.

ID:UD: So what responsibility do we as DJs, promoters, clubgoers and consumers of music have if we want better? How do we get from where we are to where we want to be?

Jairus: We have to stop celebrating marginalization and mediocrity. I don’t know how many DJs I’ve heard say that they don’t like a lot of the music they spin, they just spin it because they think it’s what everyone in the club wants to hear. The reality is that people in clubs want to hear what the DJs have taught them to expect. That’s the entire job of the DJ. The way DJs throw their hands in the air like they can’t do anything about it is infuriating. I can just imagine them as parents: “Well, I feed my kid ice cream all day but only because I don’t think he likes to eat anything else.” Fuck off. You’re the parent. Don’t buy the fucking ice cream. Don’t play the fucking Combichrist track.

The way the community came together to promote the Everything Goes Cold kickstarter was an example of things done right. EGC wanted to build a better product than Metropolis wanted to build, so they said “we’d like to do this better and we’d like to promote some other bands along the way”. And it worked. A ton of musicians, artists, promoters, DJs, and fans helped make a risky premium product a success. Metropolis wasn’t going to do it. It took a village.

“I don’t believe access to art should depend on how much money you have. I don’t believe that a trust fund teenager with an iTunes account connected to daddy’s credit card deserves more access to art than a teenager on welfare.”

ID:UD: You’re a proponent of releasing music under a Creative Commons license, and pretty outspoken on the topic of what you feel the actual effects of file-sharing are on musicians and the music industry. What personal experiences formed those views, and how do you approach the debate as someone with a position that is at odds with a lot of artists on those topics?

Jairus: My views on file-sharing are reinforced by the arts work I’ve done (in this scene and elsewhere) and by the countless studies that have been done on the topic. But they were formed through my experiences with poverty.

I grew up poor, moved out young, and was homeless for long enough that it seemed like a permanent condition. When you’re poor a lot of doors to art are closed to you. You can’t learn to play the piano if you can’t afford a piano teacher, you can’t learn to paint oils if you don’t have a home to dry the painting in, you can’t learn economics if you can’t afford the textbooks, that kind of thing. And it sucks, but there’s a logistical reality behind it. You need physical access to a piano to learn how to play the piano. You need to consume physical materials to learn how to paint. You need physical access to a book in order to get access to the information in it. There’s a scarcity of materials.

That’s not the case anymore. There is no natural scarcity with information, with music. There is only a scarcity of the physical mediums that music is carried on. You don’t need access to a CD to listen to an album anymore, all you need is the data, and you can make as many copies of the data as there are people who want it.

I don’t believe access to art should depend on how much money you have. I don’t believe that a trust fund teenager with an iTunes account connected to daddy’s credit card deserves more access to art than a teenager on welfare. The idea that the trust fund kid is “allowed” to listen to more music is so completely fucking absurd to me as to be nonsense. It’s like having a fireworks show and saying that poor people who can’t afford to pay you $20 aren’t allowed looking up at the sky because hey those fireworks aren’t cheap to make and I gotta eat, you know? It’s crazy.

I used to have a lot of time for artists who didn’t see things the same way. I don’t any more. I understand why people got spooked when file-sharing came out, and industry revenues started dropping. We didn’t know that people were deciding to spend money on games instead of music or film, or that entertainment spending overall was still rising year after year.

Ten years ago we didn’t have countless studies that showed people who pirate music spend more money on music than people who don’t. We didn’t have testimonials and case studies of how free distribution increases sales. There’s no excuse anymore, and artists have so much learned helplessness and cognitive dissonance on the issue that it’s mindblowing. Musicians complain on Facebook about people pirating their music between posting YouTube links of other people’s pirated music.

92% of teenagers don’t have a problem with downloading. That’s the future. People graduating high school this year have never known a world without Google. Think about that. Think about how meaningless the idea of ‘piracy’ is for someone who has spent their entire life being able to listen to anything they want just by typing it into their browser bar.

If artists and labels don’t understand that the game has changed, that’s their problem. They can have their tantrums. They can throw a fit and say they’re not going to make or release music anymore because everyone’s going to download it. That’s fine. Just means that every day there’s less of them. I don’t need artists to agree with me. I just need them to get out of the fucking way.

Ad·ver·sary plays Kinetik on May 17th, and will be appearing at select dates on the iVardensphere / WASTE / ESA tour this summer.

That was pretty great.

Now THIS is an interview!

This is one of the best interviews I have read in a long time. Totally engaging (and nice to hear some of this stuff being said). Thanks!

Great interview, thanks for the insights. Looking forward to Kinetik!